Zuni Pueblo

- She-we-na: The Middle Place

- Language: Zuni

- Size: 418,000 acres

- Population: About 6,500

About 35 miles south of Gallup in western New Mexico, Zuni has always been considered one of the Rio Grande Pueblos because of the similarity in history, religion and societal processes. With the largest tribal population, the Zuni reservation covers almost 700 square miles (about the size of Rhode Island), making it in both ways the largest of the pueblos. More than 3/4 of the pueblo population is involved in the production of native arts. Most people live in Zuni village itself or in the nearby community of Blackrock.

With pit houses dating back to about 700 CE, the Zunis may be the oldest individualized pueblo in New Mexico. The present Zuni village on the banks of the Zuni River has been occupied since about 1692. The Zuni speak a language unrelated to the languages of the other Pueblos. Linguists have determined their language may have diverged and come into its own between 7,000 and 8,000 years ago. That means it was probably spoken over a much larger area back then than where Zuni is spoken now. Zuni is speculated to be a descendant of a postulated "Amerind" language spoken 10,000 or more years ago among many tribes in the Americas. Uto-Aztecan is also a descendant of that ancient tongue.

The Zuni Creation Story has them entering this world through the Grand Canyon, then journeying upstream along the Little Colorado River and eventually reaching the valley of the Zuni River. Archaeologists have found a lot of evidence in support of that story.

In the 1200s, Zuni was seeing a time of plenty while the Four Corners area was seeing a severe years-long drought. The drought caused an out-migration from the Four Corners while the Zunis expanded their holdings eastward, halfway to Acoma. They built a dozen large and small pueblos along an arc through the Zuni Mountains, Atsinna being one of the larger ones. Then came a really severe drought across the entire Southwest in the mid 1300s. Those new pueblos were abandoned and their people moved back into the Zuni River basin, building at least seven large pueblos before the first Spaniard arrived in 1539.

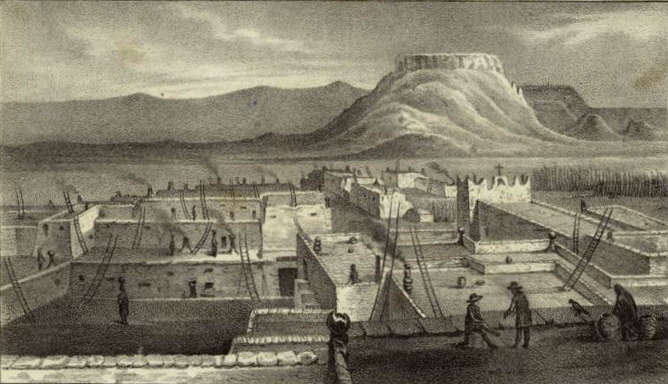

Zuni Pueblo in 1850

Post-Contact History

The first Zuni pueblo that Spanish Franciscan Father Marco de Niza and his subordinate, Esteban the Moor, encountered in 1539 was Hawikuh, the main Zuni village back then, located about ten miles southwest of the present village of Zuni. It is said the attempts of Esteban the Moor to force himself on a married Zuni woman caused a Zuni warrior to kill him almost as soon as they arrived. Father Marco returned to Mexico City shortly after, spouting tales of the riches and gold he'd found in Cibola. That led directly to Coronado and his army arriving at Hawikuh in 1540.

He arrived as the Zunis were participating in a religious festival. They had seen the Spanish coming in the distance and had dripped a trail of corn meal across the pueblo entrance to signify they weren't to be bothered until they were finished. Coronado ignored that and, at first, the Zunis ignored his attempts to enter their village. Shortly Coronado had a ladder placed against the wall and he started to climb. The Zunis responded by dropping large rocks over the wall and knocking him off the ladder. As some of his men covered him to protect him, he ordered the rest of his men to attack. The fighting didn't last long, the Zunis gave in.

Coronado didn't find any of the gold he was looking to steal but he heard tales of gold located to the east. His men raided the Zuni food stores and let their livestock destroy the Zuni gardens before they headed east to the Rio Grande. To help them on their way, the Zunis gave them a man from the far east as a guide. That guide was instructed to lead the Spanish onto the plains of Kansas and let them die there. The Spanish learned that on the plains of Kansas and strangled the man. Then, empty-handed, Coronado and his men fought their way back to Zuni and then back to Mexico.

In 1632, long before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Zunis revolted alone against the Spanish. The revolt was quickly put down and the Zunis severely punished. When the 1680 Pueblo Revolt happened, they again killed all the nearby Spanish. In fear of coming reprisals they built a fortress atop Yowa Dalanne (a nearby mesa) and retreated there until the Spanish came back in 1692. However, raids by marauding bands of Apaches and Navajos became such a problem that they almost welcomed the protection of Spanish troops in 1692. When the Don Diego de Vargas first arrived at the foot of the mesa, he negotiated with the Zunis and was allowed to ascend to the mesa top and tour the area. He found various of the implements from the mission in view and soon concluded a truce with the Zunis where they again swore allegiance to the crown and the cross, then they came down off the mesa and into the valley.

Zuni had also taken in refugees from other pueblos during that time when the Spanish were gone. By 1700, most of those refugees had returned to their homes closer to the Rio Grande but during that time, the various tribes cross-pollinated many ideas and some of the native arts saw changes very quickly.

In times of severe drought and during epidemics (brought on by European diseases), many people from Hopi also made the trek to Zuni and stayed for a few years before returning to the Hopi mesas. Those potters took many Zuni designs and pottery-making processes back to Hopi with them: it's during times at Zuni that the Hopi began to apply a white slip to their pottery (today we call it Polacca Polychrome). That and pot sherds found at the destroyed village of Awatovi led Helen Naha to perfect the process to create today's Hopi white ware.

Zuni features a large mission church, Our Lady of Guadalupe, that was dedicated in 1629. The church underwent extensive restoration in the 1960s. The inside walls feature 24 murals of traditional kachina dancers placed above the Stations of the Cross. The pueblo is well known for the annual Shalako ceremony and dance that occurs every year in late November or early December. Ceremonies begin in the evening and the dancing goes on until noon the next day, no matter what the weather is doing.

The pueblo today consists of adobe house blocks, modern sandstone dwellings, plazas, hornos (traditional outdoor baking ovens), waffle gardens (named for their unique irrigation system) and livestock corrals. The pueblo is open daily from dawn to dusk for visitors but is closed for religious ceremonies. Official permission is required before photographs can be taken.

The village of Sichomovi on Hopi Second Mesa was founded as a Zuni village. The Zuni people also purchased a ranch in eastern Arizona where archaeologists found some of their more ancient pueblos. They made a foot trail alongside the Zuni River that connects that ranch with Zuni Reservation proper. Some Zunis often run that trail and visit with their ancestors as part of their spiritual practice.

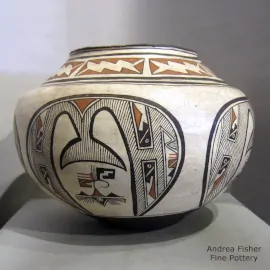

Pottery History

Zuni pottery tends to be colored with black, brown or red paint on a white or red slip. A few of the most common designs include deer with heartlines, rainbirds, flowers, feathers and fine-line cross-hatching. Like Acoma and Laguna potters, Zuni potters use crushed potshards to temper their clay.

There was a time before 1700 when some Zuni potters decorated their pottery with lead-based paints. Potters in the area around the Cerrillos Hills were doing the same. However, the lead sources in the Cerrillos Hills were seized by the Spanish in 1692 and that source of support for those pueblos ceased to exist. They were all abandoned shortly. The Zunis, instead, lost their collective memory of their own local lead source and denied that knowledge to the Spanish. They also stopped making lead-glazed pottery then.

In the 1700s Zuni potters switched to using mineral and vegetal matte paint for their decorative designs. Scholars and collectors know this as "Ashiwi Polychrome." A rare style found today among the Zuni is a white on red pottery that is believed to be a traditional style from prehistoric times. That white on red was created using a reddish color slip and decorated with motifs in white paint. Some examples of this style can be found as late as 1900.

By the 1940s, little Zuni pottery was being produced. And that pottery was mostly made for ceremonial purposes. One woman, Catalina Zunie, kept the tradition alive at Zuni High School until she passed the torch to a Hopi potter named Daisy Hooee in 1960. That seems to be where the real revival of Zuni pottery making began.

Daisy was a daughter of Annie Healing Nampeyo and granddaughter of the famous Hopi potter Nampeyo of Hano. She received an arts scholarship in the 1920s and studied ceramics for 2 years at L'Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. After she returned to the United States Daisy moved around for a few years before she met and married Sidney Hooee, a Zuni jewelry maker. They lived at Zuni Pueblo.

Before she agreed to teach the class, Daisy made herself into a consummate Zuni potter. She began teaching pottery at Zuni High School in 1960 and retired in 1974. She did still keep teaching pottery making in her home, mostly to older women. She reintroduced the traditional methods she had learned from her mother and grandmother.

After Daisy came Jennie Laate, also teaching at Zuni High School. Many of today's most prominent Zuni potters trace their learning back to Jennie. Jennie taught from 1974 to 1990. In that time period, Zuni Potter Josephine Nahohai was granted a fellowship from the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe. With that stipend she made a trip to the Smithsonian Institute and the Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC. There, she and her sons Randy and Milford, studied and copied traditional Zuni designs from archaeological findings and museum pieces. They then brought those ancient designs back into Zuni pottery making.

Noreen Simplicio continued the pottery classes at Zuni High School from 1990 to 1992, and for both years she had more than a hundred students in her classes. Because so many Zuni potters learned their art at school, use of the commercial pottery kiln has become commonplace. Noreen retired in 1992 and Gabriel Paloma took over teaching the Zuni High School classes.

Contemporary Zuni pottery includes a large variety of shapes and forms using traditional water and rain figures, like tadpoles and frogs. Ceramic figures of owls, ducks and fish are also popular.

Zuni artisans are also famous for their turquoise and silver jewelry. The materials they use to make their intricate inlaid jewelry include coral, jet, mother of pearl and seashell. Some artisans also produce carved stone fetishes of animal figures and kachinas.

Zuni landscape

Lower image is courtesy of eyesofthepot, CCA 4.0 License