Tesuque Pueblo

- Te Tsugeh Oweengeh: Village of the Narrow Place of Cottonwood Trees

- Language: Tewa

- Size: 17,000 Acres

- Population: About 400

Tesuque Pueblo is located about 10 miles north of Santa Fe near Camel Rock, a large, naturally eroded sandstone rock formation. Archaeological sites in the Tesuque Valley area have been dated back to 850 CE. By 1200 CE there were many villages in the area. When the Spanish arrived in 1541 they found six villages including the original Tesuque village, which was located about 3 miles east of today's village.

Tesuque warriors struck the first blow during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 when two of their messengers were captured by the Spanish and forced to reveal plans about the upcoming revolt. As soon as the messengers told the Spanish the planned date for the uprising to begin, they were put to death. Too bad they had been given the wrong date... Back on the pueblo Tesuque warriors responded by killing a Catholic priest and a public official the next day.

During the Spanish re-conquest in 1692, the old village of Tesuque was virtually destroyed. After submitting to the Spanish, the Tesuque people abandoned the ruin of the old village and moved to their present site in 1694.

Pottery History

Once upon a time Tesuque potters made lots of pottery using the same clay and slip as their Tewa neighbors in nearby San Ildefonso. In those days that was black-on-cream pottery plus a bit of polychrome ware. Tesuque pottery tended to have a more rippled surface with flatter bases, and sometimes crystalline fragments in the paste.

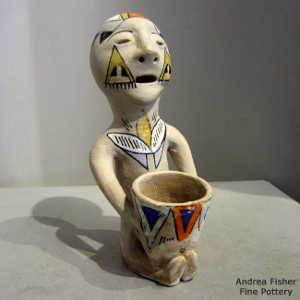

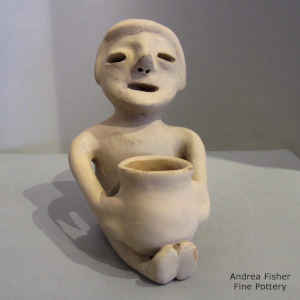

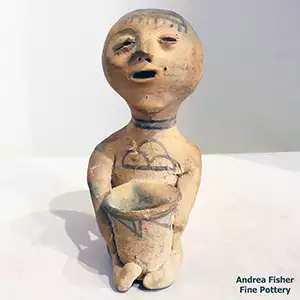

In the 1830s the Tesuque style began to change and Tesuque Polychrome evolved. That was quite popular until the 1880s when a trader named Jake Gold convinced Tesuque potters to make small figures they called Muna and he called "Rain Gods." Gold also had them decorate the Rain Gods with commercial paint. These Rain Gods were neither traditional nor ceremonial figures and were made purely for the tourist market. Mr. Gold did an outstanding job of marketing and soon Tesuque potters were turning them out by the thousands. Rain Gods were distributed nationwide. They could be bought by the barrel and thousands were given away by manufacturers as promotional items.

The mass production of Rain Gods essentially ended the making of traditional pottery at Tesuque. Then in the 1930s the demand dropped off for the figures and the pueblo potters turned to producing small, usually low fired pots painted with commercial poster paint. Catherine Vigil was among the rare potters still making traditional polychrome ware through the 1930s and 1940s. In the 1960s a few pueblo potters went back to making traditional micaceous pieces and polychrome ware. Today there are still a few potters working to bring back the traditional way of producing authentic Tesuque pottery.