Zia Pueblo

- Tsia

- Language: Eastern Keres

- Size: 122,000 acres

- Population: About 800

The Zia people have occupied their land since the 1200s after migrating from the Four Corners area. Zia oral history indicates they have been a persistent tribal entity since the days when their ancestors inhabited Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon (before the pueblos at Mesa Verde were built). The rocky nature of their landscape has made farming difficult so for many years they have traded pottery ollas and bowls to other pueblos for agricultural products.

The Spanish first came in 1540 but they found no gold so they left. They came back several times over the years and in 1598, the Franciscan fathers estimated the population of Zia Pueblo at about 2,500 people. The mission church, Nuestra Senora de la Asuncion, was dedicated in 1612.

Like most other pueblos the people of Zia participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and they partially destroyed the mission church in that process. When Domingo Cruzate invaded New Mexico in 1688 in an abortive mission to retake the province for Spain, he attacked both Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos. He succeeded in killing more than 600 Zias and captured many others that he took back to Mexico as slaves. Those who escaped the carnage fled into the mountains to hide. Cruzate burned the Zia village, then returned to Mexico. (I've always been amazed at how brutal the "civilized Christian Spaniards" were.)

The surviving Zias went up into the mountains and canyons of the Gallinas area. They built small pueblos and made small amounts of pottery while they were there. A cache of their pottery from those days was found with about 15 pieces almost entirely whole. They have been named "Puname" and are the only extant pottery made by the Zia people before 1700 (that's where the "Puname" label on historical maps came from).

The Spanish returned in 1692 under Don Diego de Vargas. They retook Zia and the partially destroyed mission church was restored a few years later. The tribe never really recovered and the remaining population was severely affected by other marauding tribes and by diseases introduced by the Spanish and other Europeans. Once one of the largest and most powerful of the pueblos, by the 1890s the population was down to 98. What kept them alive through those years was their pottery: they traded excellent pottery to their neighbors for food. For 200 years after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt the Zias produced most of the pottery used by the Jemez, the Santa Anas and themselves.

Today, Zia has two plazas, each with its own kiva. The plazas are surrounded with one-and-two-story buildings made in the traditional way: native rock walls plastered with adobe mud. Zia is a living pueblo and no photos, recordings or sketching is allowed. The pueblo tends to be open for visits daily from dawn to dusk but is closed during religious ceremonies.

Today's Zia Pueblo is surrounded by the ruins of at least half-a-dozen older pueblos, testiminy to the movements of the people over hundreds of years. As they are all on pueblo land and close to a living pueblo, virtually none of them has been excavated or investigated by archaeologists or ethnographers.

A view on Zia Pueblo

Pottery History

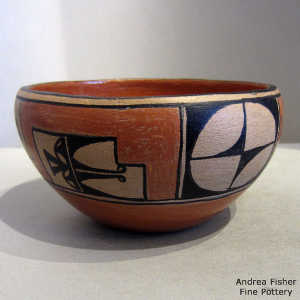

Zia's pottery has been made from brick red clay, tempered with crushed basaltic rock and hard-fired for several hundred years. A white slip was added to the process a couple hundred years ago. The product is durable, as evidenced by the large number of older surviving pots. Their pottery is very similar in style and design to that of Acoma except that Zia pots have thicker walls and are overall much heavier. They also prefer very stylized designs of birds and water with red and black arches (rainbow patterns). The Acoma and Laguna bird is the parrot while the Zia bird is the roadrunner.

The arrival of tourists on the railroads in the late 1800s may have influenced Zia bird designs to become more natural as their roadrunners became more recognizable as roadrunners. Also highly recognizable is the Zia "Sun" symbol, taken from a ceremonial jar that had been stolen from the tribe's cacique in the early 1890s.

In the 1890s, James and Matilda Stephenson changed their focus from Zuni to Zia. James was negotiating to purchase a sacred water jar with the Sun sign on it when he suddenly died. Shortly after, Matilda packed up and moved back to their home in Washington DC. About the same time she left, the sacred water jar disappeared. A few years later it showed up at the School for American Research (now the School for Advanced Research) in Santa Fe. I think the jar was finally returned to the Zias in 2000.

This story was very typical of those years when the tribes had to deal with an onslaught of erstwhile American and European "archaeologists" and "ethnographers". The "ethnographers" and "archaeologists" were intent on removing and preserving every artifact of the dead and dying Native cultures in the Southwest. They were convinced they were doing good, they were saving the tribe's history, dances and cultural patrimony. Their efforts removed so much of Native American ceremonial patrimony that some tribes lost virtually all connection with their past. With all their stated good intentions, the Americans and Europeans almost finished the job begun by Spanish religious zealots and military authorities in the 1500s.

Today, Zia potters are still making clay products in the traditional manner using traditional designs. Among those potters are the Toribio, Medina, Gachupin and Pino families.