Cochiti Pueblo

- Katyete or Ko-chits: Stone Kiva

- Language: Eastern Keres

- Size: 175 Square Miles

- Population: 1500

Located about 25 miles southwest of Santa Fe in north-central New Mexico, Cochiti (with Santo Domingo) is the most northern of the Eastern Keres-speaking pueblos. Some anthropologists and archaeologists feel the tribe originally came from Tyuonyi (a long-abandoned Ancestral Puebloan settlement in Frijole Canyon on the edge of the Jemez Mountains in what is now Bandelier National Monument) and migrated to their present location sometime between 1200 and 1500 AD. They had migrated from the Four Corners area through the San Juan River basin to where they crossed over the ridge to the Jemez River basin and then down to the Pajarito Plateau in the mid and late 1200s.

In those days, the people of Cochiti and Santo Domimngo were one tribe. The division came when it became time to cross the Rio Grande after they moved down from the Pajarito Plateau. The people of Santo Domingo crossed the river, the people of Cochiti did not. From that point on, the cultures and religions of the two tribes began to diverge.

Tyuonyi pueblo in Frijole Canyon

The first Spaniard the Cochitis met was Frey Rodriguez when he arrived to set up a mission in 1581. The San Buenaventura Mission church was built around 1630 and saw regular use until it was burned in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

After the Pueblo Revolt, the inhabitants of Cochiti and Santo Domingo worked together and set up a hidden mountain stronghold at Cieneguilla. The Spanish returned to northern New Mexico in force in 1692 and attacked Cieneguilla the following year. Many of the warriors were killed in the fighting and a majority of the survivors were returned to Cochiti village and put to work constructing a new mission church that still stands today. Those who managed to escape from the Spanish attack joined those refugees who established the new pueblo at Laguna in 1699.

Frijole Canyon, an ancestral home of the Cochiti people

Cochiti Pottery History

Cochiti and Santo Domingo had long developed their pottery on a parallel course until about 1830, when the Cochiti potters began a 20-year evolution away from the Kewa Polychrome of Santo Domingo to their own distinctive style known as Cochiti Polychrome. The initial differences between Kewa and Cochiti Polychrome are seen mainly in the designs used. Cochiti Polychrome design lines became lighter and finer with motifs often becoming isolated decorations unrelated to one another. Kewa Polychrome designs consisted of heavy, bold lines with multiple geometric patterns. Secular Cochiti Polychrome pottery also often contains sacred symbols such as clouds, rain, lightning, serpents, mammals and humans, all of which were/are strictly forbidden to Santo Domingo potters.

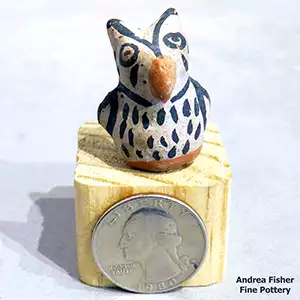

In addition to their traditional pottery, Cochiti potters also produce ceramic animal figurines in the form of owls, turtles, bears, frogs, coyotes and other animals, many of which are quite popular with the tourists. In the 1880s, a delegation of Cochiti men got on the train and went to Washington, DC. They met the President and spoke to Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Then they traveled to New York City. There they went to Madison Square Garden and saw the Ringling Brothers Circus. They also went to the Bronx Zoo and to the Metropolitan Opera. No one could read or write, no one had pen or paper, no one drew anything. So when they returned to Cochiti, some of the stories of what they saw got pretty fantastical. Today, we're seeing pottery figurines built from memories of the attributes of various circus animals and performers that were first seen in the 1880s.

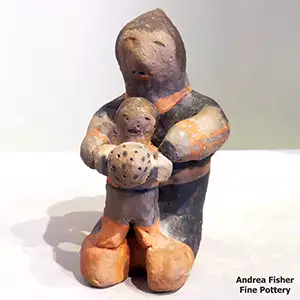

One of the most popular pottery figurines that originated at Cochiti is the storyteller, a design made famous by Helen Cordero. Today, Cochiti potters make an enormous variety of storyteller figures in the forms of animals and humans. Although Cochiti has long been known for producing storytellers and traditional drums they also have talented jewelers and painters.