Tonto Basin

One of the pueblos of Tonto National Monument

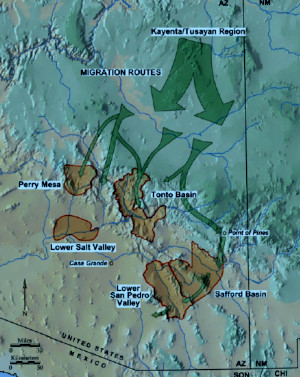

Migration routes of the

Kayenta-Tusayan potters

The earliest settlers in the Tonto Basin were most likely migrants from the Hohokam core areas around what are now Phoenix and Tucson. Tens of thousands of people tended hundreds of miles of irrigation canals in those basins but after several hundred years of use, everything was silting up and water levels were dropping. People started looking for greener pastures in other areas.

The early settlers in the Tonto Basin soon evolved their own vibrant culture. They made beautiful pots, painted with elegant, curved designs suggestive of bird wings and sunbursts. Those pots were traded and emulated all across the Southwest. They built great food storehouses, reaping the bounty of a frost-free climate that offered rich wild plant resources plus three plantings a year.

They buried their dead reverently, along with possessions treasured in life, usually close by their settlements. In one place, archaeologists unearthed the simple burial of a man interred with his potter's tools and a lump of unworked clay. Often, the Salado buried their babies in the floors of their homes, as though the family sought to protect the spirit of someone too young to have mastered death on their own.

Like every other agglomeration of human beings, Salado society grew increasingly complex and stratified over time. They farmed 44 miles (70.8 km) of the Gila River streambed in the Tonto Basin. Many lines of evidence converge in their culture: the changeover from just building largely ceremonial platform mounds to operating bustling food storehouses. There were the first signs of upper-class houses built on top of the mounds. There were concentrations of weapons and precious stones like turquoise found at the later mounds. As the population grew there was an increasing reliance on irrigated crops. And like every other developing society, there was the emergence of specialists, like potters.

Then their complex civilization collapsed in a matter of a few decades. There were no major shifts in the waterflow that coincided with the abandonment. That rules out flood destroying the irrigation systems or drought not providing enough rain water. According to tree-ring studies, the 1400s brought no serious droughts to the area. Small droughts came and went but that's normal in a watershed where the runoff varies every year from 162,000 acre feet to 2.6 million acre feet (an acre foot is enough water to cover one acre to a depth of one foot). The Salado weathered many such variations during the centuries they occupied the valley.

Archaeological evidence suggests the Salado could have been done in by a disaster of their own making. Perhaps their population outgrew the ability of the resources of the basin to support them. They were affected by the collapse of the Hohokam civilization to the west as it brought a lot more people into the basin. There could have been an epidemic, too. Or warfare with one another or with outside groups may have caused their society to become more divided and class conscious.

Archaeologists have found one instance hinting that increased warfare played a tragic role in Salado society. They found burned roof beams lying in disorder on the floor of a structure. Then they found an arrow point embedded in what had been a doorway. Then, trapped beneath the burned roof beams they found three skeletons lying facedown on what had been the floor of their home. Other evidence indicated their settlement had been raided. The waist-high walls of their pithouse would have provided little protection from determined raiders. They took refuge in their home, only to have the raiders set it on fire.

The settlers who first entered the Tonto Basin in the 700s and 800s were coming from the Hohokam settlements downstream on the Salt River. They were attracted to the Tonto Basin by the irrigation potential.

In the beginning, the Tonto Creek arm was occupied primarily by local groups that had developed connections with both Hohokam and nearby Mogollon peoples. By 1100, there was a major change in exchange networks throughout the basin: Cibola whiteware pottery, made on the Colorado Plateau to the north and east replaced imported Hohokam buffware made in the lower Salt River Valley.

By the early 1200s, many small irrigation communities had claimed most of the prime agricultural land in the basin. Settlements had been built on nearly every ridge overlooking the Salt and Tonto floodplains. Then in the late 1200s immigrants from the Kayenta-Tusayan tradition entered the region, bringing their corrugated ceramics and roomblock architectural styles with them. These groups settled on the edges of local communities and filled the rest of the habitable upland areas. Many local communities in the basin built platform mounds that served as both ceremonial centers and territorial markers.

The 1400s were a time of great movement and consolidation in the Southwest. It was also the time of entry of the Utes, Apaches and Navajos to the scene. By 1500, Apache tribes were in control of the Tonto Basin after pushing the Salado out. Following the pottery trail, many of the Salado potters moved further south, to the San Pedro River Valley and into northern Mexico. They weren't going to Paquimé as that famous pottery-making city was being abandoned, too, its citizens reportedly migrating over the mountains to the west into Yaqui territory.

Salado shapes and designs had migrated to the Rio Grande Valley years before and derivatives were being produced locally there. Archaeologists have found Salado pottery, made in the Tonto Basin, from the Pacific Ocean to the Rio Grande and from northern Mexico to central Utah.

The upper cliff dwelling of Tonto National Monument

Sites of the Ancients and approximate dates of occupation:

Atsinna : 1275-1350

Awat'ovi : 1200-1701

Aztec : 1100-1275

Bandelier : 1200-1500

Betatakin : 1275-1300

Casa Malpais : 1260-1420

Chaco Canyon : 850-1145

Fourmile Ranch : 1276-1450

Giusewa : 1560-1680

Hawikuh : 1400-1680

Homol'ovi : 1100-1400

Hovenweep : 50-1350

Jeddito : 800-1700

Kawaika'a : 1375-1580

Kuaua : 325-1580

Mesa Verde : 600-1275

Montezuma Castle : 1200-1400

Payupki : 1680-1745

Poshuouingeh : 1375-1500

Pottery Mound : 1320-1550

Puyé : 1200-1580

Snaketown : 300 BCE-1050

Tonto Basin : 700-1450

Tuzigoot : 1125-1400

Wupatki/Wukoki : 500-1225

Wupatupqa : 1100-1250

Yucca House : 1100-1275