Betatakin

Betatakin

Looking at the ruins from

beneath the overhang

Betatakin is a Navajo word meaning "House built on a ledge." The Hopi name is Talastima, meaning "Place of the Corn Tassel."

Located in an arm of Tsegi Canyon, Betatakin is part of the Kayenta-Tusayan historic area. The pueblo was abandoned well before the Navajo came into this countryside.

Betatakin consisted of about 120 rooms and one kiva. Because of rock fall over the years, only about 80 rooms can still be accessed.

Dendochronologists have determined that logs to build the pueblo were stockpiled on-site between 1269 and 1272. Then there was a burst of constriuuction between 1275 and 1277. At that point, an entire village moved in in an orderly fashion and lived there for a couple decades, Then they began leaving the area until it was finally compleltely abandoned before 1300. At its height Betatakin consisted of about 120 rooms and one kiva. The maximum population was maybe 120 people.

The lifetime of Betatakin was about the same time period as the Great Drought, from 1276 to 1298. This was a long term drought that affected people all over the Four Corners area. It was one of the principal reasons leading to the final abandonment of Mesa Verde, Yucca House, Aztec and Hovenweep.

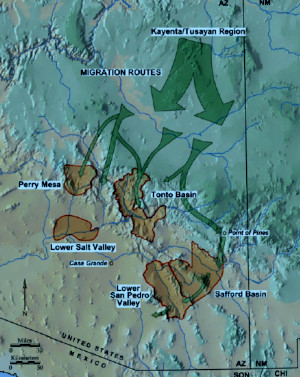

Migration routes followed by the

Kayenta people in the late 1200s CE

Tsegi Canyon may have been better for the people early on in the drought because each of the pueblos built in plenty of grain storage space as they were being built. However, as the drought wore on, more and more people entered the area looking for food and things got rough. Eventually, it got to be too much and many of the remaining people migrated to either the Hopi mesas or down the Colorado River to Havasupai.

Others went south to the Homol'ovi and Fourmile areas, too, but that didn't last long as those folks were also moving out in the face of bad weather. There has also been a Kayenta migration tracked going further to the south, essentially becoming the Salado culture in the Tonto Basin and, through their pottery and their obsidian trade, they have been traced from there going as far south as Paquimé and into the Pacific coast area in central Mexico. Like many other small cultures of the time, some returned to their ancient homelands while the rest faded into the local background and essentially disappeared during the climate events of the mid-1400s. We know where they went by following the trail of perforated plates they left behind (perforated plates are uniquely a Kayenta innovation for the making of pottery).

Tsegi Canyon

Looking down on Betatakin from the canyon rim

Pictographs on a canyon wall near Betatakin

Map courtesy of Archaeology Southwest

Sites of the Ancients and approximate dates of occupation:

Atsinna : 1275-1350

Awat'ovi : 1200-1701

Aztec : 1100-1275

Bandelier : 1200-1500

Betatakin : 1275-1300

Casa Malpais : 1260-1420

Chaco Canyon : 850-1145

Fourmile Ranch : 1276-1450

Giusewa : 1560-1680

Hawikuh : 1400-1680

Homol'ovi : 1100-1400

Hovenweep : 50-1350

Jeddito : 800-1700

Kawaika'a : 1375-1580

Kuaua : 325-1580

Mesa Verde : 600-1275

Montezuma Castle : 1200-1400

Payupki : 1680-1745

Poshuouingeh : 1375-1500

Pottery Mound : 1320-1550

Puyé : 1200-1580

Snaketown : 300 BCE-1050

Tonto Basin : 700-1450

Tuzigoot : 1125-1400

Wupatki/Wukoki : 500-1225

Wupatupqa : 1100-1250

Yucca House : 1100-1275