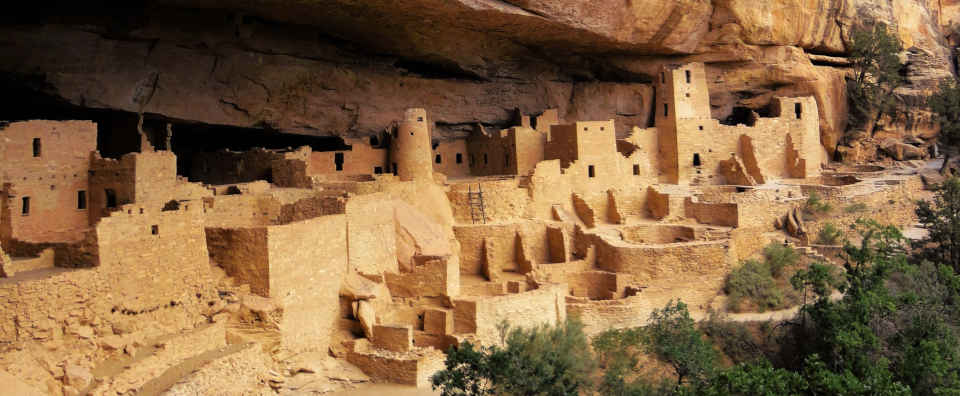

Mesa Verde

The culture represented at Mesa Verde reflects more than 700 years of pre-Columbian history. From approximately 600 through 1300 CE, people lived and flourished in communities throughout the area, eventually building elaborate stone villages in the sheltered alcoves of the canyon walls. There was a slow but steady population growth through the 800s and into the 900s, then there was population shift and abandonment of some areas. Then came a period of reoccupation and new construction in the 1000s, followed by a collapse and reorganization in the 1100s. There was a turbulent period in the 1200s as pueblos moved to more defensive positions and they started raiding each other for food. Then, from 1276 to 1285, came a time of rapid depopulation as a deep drought set in and the area was abandoned.

The archaeological sites found in Mesa Verde are some of the most notable and best preserved in the United States. Archaeologists study the ancient dwellings of Mesa Verde, in part, by making comparisons between the Ancestral Pueblo people and their contemporary indigenous descendants who still live in the Southwest. Twenty-four Native American tribes have an ancestral affiliation with sites in the Mesa Verde area.

Today most people call these sheltered villages "cliff dwellings". The cliff dwellings represent only the last 75 to 100 years of occupation at Mesa Verde. In the late 1200s, within the span of one or two generations these people were forced by a change in the weather to leave their homes and walk away. Some speculate that it was a change in religion, too, because when they walked away, they left almost everything behind and began again almost totally new. Architecture, rock art, spiritual practices, pottery decorations and the people's general worldview changed almost completely in one generation. And they literally walked away from the old.

Cliff Palace

- Dates of Occupation at Mesa Verde

- Far View House - ended 1078

- Oak Tree House - 1055-1184

- Pipe Shrine House - ended 1214+

- Hemenway House - 1110-1184

- Square Tower House - 1066-1259

- Mug House - 1032-1262

- Spring House - ended 1273

- Cliff Palace - 1073-1273

- Spruce Tree House - 1020-1274

- Balcony House - ended 1279

- Long House - 1024-1280

There is evidence the Mesa Verde area was first populated about 8,000 years ago. When the temperature rose about 7,000 years ago, the population in the entire region rose dramatically. With the introduction of a good maize kernel about 3,000 years ago, larger population centers grew in the lowlands around the mesa. Atlatls for hunting were in use and the Basketmaker I period was giving way to the Basketmaker II period. Then around 500 CE the Basketmaker II period gave way to Basketmaker III. Atlatls were being swapped for bow and arrow, baskets were being swapped for pottery. By about 600 CE, the people were doing their cooking in clay pots and gathering in small communities of pithouses.

The first pueblos (marking the beginning of the Pueblo I period) were probably started around 650 CE but most people still lived in pithouses for another couple hundred years. There might have been about 1,500 people on the mesa when new varieties of beans and corn were introduced around 700 CE. By 850 CE, more than half the people on the mesa lived in stone dwellings above ground. Most remaining pithouses had become either kivas for one ceremony or another or storage rooms for food. Maybe half of the interior space of a pueblo was used for grain storage as the people tried to hoard enough grain to last through at least three years in case of drought. By about 860 CE, there were around 8,000 people living in the Mesa Verde area but by 880, the population was in steady decline: the irregular rainfall had turned against the people and they were too dependent on it. The majority of people at Mesa Verde migrated south and took up residence around Chaco Canyon. In 950 CE, by scientific agreement, the archaeological time clock turned over: Pueblo I became Pueblo II.

For 200 years of the Pueblo II period, Chaco Canyon was the primary center of Ancestral Puebloan culture. There were still people living at Mesa Verde but the population was way down until the rainfall began to pick up in the early 1000s CE. By 1050 people began migrating back to Mesa Verde from Chaco.

Around 1075 the people began building the first Chaco-style masonry buildings at Mesa Verde. Far View House, the largest of these, is thought to be a classic Chaco outlier on which construction began somewhere between 1075 and 1125 CE. Then drought set in again down south and by 1150, Chaco Canyon was almost completely deserted.

Many of the people from Chaco moved north to the new pueblo built beside the Animas River at Aztec. Others continued on past Aztec and returned to Mesa Verde.

Major construction at Mesa Verde was paused from about 1175 to about 1190, then several multi-storied stone buildings with hundreds of rooms for hundreds of inhabitants were built. There were maybe 22,000 people living in the Mesa Verde area in 1200. The population boomed again from 1225 to 1260 as the Aztec area was being abandoned. By 1250 more than half the people at Mesa Verde were living in large, multi-story stone structures built into the cliffs and under overhangs. They farmed plots of land in the flood plains below the pueblos and kept at least three years of surplus food in their storage rooms. Then the Great Drought hit the Colorado Plateau in earnest in 1276. For a few years construction was funneled into building defensive stone towers and walls around each of the Great Houses as the pueblos raided each other for food and grain. Then all construction stopped and the people started to leave in droves.

By 1285 the Mesa Verde area was almost deserted. The majority of the folks headed southeast to the Jemez Mountains, Chama River Valley, Pajarito Plateau and the northern Rio Grande region. Others opted to go southwest to the Hopi mesas or further south to the Zuni River valley. The landscape they left was open and empty for a hundred years, then the Utes moved in. Right behind them came the Navajos, Apaches and Spanish.

The incoming Native Americans found lots of ancient ruins but they left virtually all the ruins they found undisturbed. Then in the 1880's Euro-American explorers started to find cliff dwellings in the lower canyons. It wasn't until 1888 that Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason discovered Cliff Palace and really let the cat out of the bag. That set off almost 20 years of continuous looting of this area of indigenous history before President Theodore Roosevelt created Mesa Verde National Park in 1906 to protect the artifacts still left and the ancient pueblos that still rise above them. Ruins at Betatakin, Keet Seel and other areas on the Colorado Plateau had to be protected the same way, for the same reasons, after being left undisturbed by the Navajo for hundreds of years.

Richard Wetherill had a hand in the later discoveries (and subsequent looting) of Keet Siel and Betatakin but the name he made for himself forced him out of the area. He moved to a ranch on the outskirts of Chaco Canyon. He grazed cattle in the canyon while he explored there for years. Some say he made some pretty good money under the counter, selling some of what he found among the ruins of the Great Houses.

Square Tower House

Upper photo of Mancos black-on-white pitcher courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, CCA-by-SA 4.0 License

Lower photo of Mesa Verde back-on-white mug is in the public domain

Maps built on base courtesy of Wikipedia userid Yuchitown, CCA-by-SA 4.0 License

Sites of the Ancients and approximate dates of occupation:

Atsinna : 1275-1350

Awat'ovi : 1200-1701

Aztec : 1100-1275

Bandelier : 1200-1500

Betatakin : 1275-1300

Casa Malpais : 1260-1420

Chaco Canyon : 850-1145

Fourmile Ranch : 1276-1450

Giusewa : 1560-1680

Hawikuh : 1400-1680

Homol'ovi : 1100-1400

Hovenweep : 50-1350

Jeddito : 800-1700

Kawaika'a : 1375-1580

Kuaua : 325-1580

Mesa Verde : 600-1275

Montezuma Castle : 1200-1400

Payupki : 1680-1745

Poshuouingeh : 1375-1500

Pottery Mound : 1320-1550

Puyé : 1200-1580

Snaketown : 300 BCE-1050

Tonto Basin : 700-1450

Tuzigoot : 1125-1400

Wupatki/Wukoki : 500-1225

Wupatupqa : 1100-1250

Yucca House : 1100-1275