A Journey into the World of Native American Pottery

Pottery has a sensuality to it, a physical and emotional feel. There is also a spiritual element involved as for virtually all traditional Native American potters, there are prayers being uttered throughout their process, different prayers for each stage of their process, from before the digging of the clay to after the firing. And nearly all will tell you they are only trying to do what Clay Mother asks of them.

Most of the story that follows in this website is centered around the Pueblo people of the Southwest. They have populated the same mountains, valleys and deserts for more than two thousand years. As they developed irrigation and agriculture and became a sedentary people, they developed a pottery tradition. That began more than 1500 years ago and it has grown over the years since.

I built this website to educate myself after taking on the job of webmaster at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery in Santa Fe, NM. The web work was simple but I felt the need to educate myself more on the product in order to present it properly. That turned into a labor of love. Now, ten years later, I look back through this site and sigh, because I've learned so much more than what's on display here. And I feel I have to bite the bullet and rewrite so much of the basic data because so much of it is based on data available more than twenty years ago. Research has been ongoing, research into life in the old days and what was happening among the puebloans between six hundred and two thousand years ago.

Some data hinting at this has been entered here over the years but not to the depth I have available now. I don't speak the languages, I don't know the dances, I can't directly interpret the symbology, but I can tell a good part of their macro life stories as to where they came from, how they built, how they farmed, what they ate, what they traded with who, where they gathered together, why they gathered there and why they stopped. Much of the story is derived from what the ancients considered "trash," but it is based on what they considered sacred, too.

Archaeologists trace the migrations of the people through the styles and designs on the potsherds they left behind, and the ancients abandoned pueblos all over the countryside. In some cases, dates of innovations in shapes, designs, technology and methods of decorating can be determined down to the decade several hundred years ago. Today, Pueblo pottery has become a highly collectable art form as designs and shapes have proliferated and quality risen sky-high. That's what this website story is about: what this art is, how it came to be, who makes it now.

The quality of a culture's pottery indicates a lot about the maturity and prosperity of the culture that developed it. When times are good, pottery develops many different styles and forms. Surface decorations also develop and proliferate. When times are not so good we see less pottery, and it's often of less quality. Sometimes we also see the merging of different lines, such as when many Hopi migrated to Zuni in the 1880s to wait out a drought and a smallpox outbreak in their homeland. When the Hopi returned to their mesas, the potters brought the use of the Zuni white slip back with them. Many Hopi-Tewa potters were still trying to adapt the Hopi version of that white slip while Nampeyo was perfecting her process with Jeddito yellow clay and using ancient designs from Sikyátki and Awatovi. When her art took off in the marketplace, many other Hopi-Tewa potters switched over to what she was doing while a few modified their process with the Hopi white slip and achieved a result that compared much better with the Jeddito yellow clay results: Jeddito yellow clay has no slip, it gets polished and decorations are applied directly to the clay body before firing. Some of the coloring of Jeddito yellow clay pieces comes from variations in the firing process. The Hopi white slip process (used mainly by the Naha and Navasie families these days) creates a very white canvas to paint mostly red and black decorations on (although some use other colors, too). Helen Naha finally perfected the process in the early 1950s and taught her children how to do it. Care is taken in firing to allow no color variation from the fire. That said, making white wares the new way, with an uncrackled white slip, is much harder to do.

Different from many other art forms, pottery is something you can pick up and feel. If you are really sensitive and in tune, you can often feel the energy of the potter who made it... It's a phenomenon I especially see when "in tune" people touch pieces made by someone like Nampeyo of Hano. I've seen it with pieces made by other potters, too, but I have seen the phenomenon most pronounced with Nampeyo's pottery. For that matter, when working to ascertain who really created any older Hopi piece we have achieved the best results by asking descendants of various Hopi potters to offer their opinions.

"That pot was made by Grace [Chapella]. She lived next door to Grandma. Grandma used to baby sit Grace as a kid, then she taught her how to make pottery." This is from a great-great-granddaughter of Nampeyo of Hano after she looked over a maybe 100-year-old unsigned pot that might have been made by Nampeyo. The piece was missing that extra coil of clay around the opening, the decorations were similar to but had embellishments that were not normal for Nampeyo and the spirit in the clay was not Nampeyo's. As that modern-day potter told us, the jar was made by Grace.

Why it Began

Southwestern Native American pottery has a legacy dating back at least 3,500 years. It's still a mystery as to how someone discovered that clay, when heated to a high enough temperature, would transform into a solid, brittle object that holds its shape. Some scholars claim the technique was brought to the early Southwest by settlers from Mesoamerica. Others contend that pottery making originated independently in the Southwestern cultures. One possibility for the discovery of the technique is that early cultures lined their cooking baskets with soft mud that would dry and harden and create a better and more durable surface on which to cook. The archaeological record somewhat supports this theory as early vessels have been found with the imprint of woven baskets texturing their outer surfaces. But the technology of firing a clay shape to make a hard container seems to have appeared all across the southern part of the United States (from Florida to the Mojave Desert) at about the same time.

There also appear to be relatively direct connections to the Mesoamerica area when we look at many of the designs that are still in use today. A lot looks to have sprung from what's been termed the "Flower World" ideology that is said to have originated in the area of Teotihuacan, in the highlands of central Mexico. Many of the images from that complex have made their way into Puebloan imagery and are still being reproduced today across the Southwestern landscape. Most of that imagery has been incorporated into modern Puebloan religions (including various flavors of Christianity, as practiced among the Pueblo people). The "last mile" carriage of the principles and imagery were likely to have been carried from Paquimé north via traders (and possibly pilgrims) returning from their journeys to the south, from the 1100s to the 1400s. The Flower World imagery and its accompanying ideology may have been carried east and south from the Mesa Verde area to the Rio Grande and Rio Puerco areas of New Mexico in the mass migrations out of the Mesa Verde area in the latter 1200s.

Many from the Four Corners and Kayenta areas went to the Hopi mesas instead. Others jumped past there and went to the Little Colorado River, Sinagua lands and further south. It was Kayenta potters who marked their trail south to the Tonto Basin, the Gila River basin, the San Pedro River basin and ultimately, to Paquimé. Descendants of those migrating peoples then returned to the Hopi mesas and, in the early 1400s CE, doubled the existing population there. Hopi oral history indicates there was a final "Gathering of the Clans" that has been dated to the mid 1400s CE. That's the time when the Núutungkwisinom returned to the Hopi mesas from Paquimé and began their long integration into what is now Hopi society.

Even Earlier Roots

A ceramic bottle from the

civilisation of Cupisnique in Peru,

made between 1,000 and 800 BCE

More research on my part has pointed to archaeological sites in northern Peru where cotton may have been first purposely grown (sometime between about 12,000 and 4,500 BCE), where the earliest irrigation systems were built (up to about 4,700 years BCE), where some of the modern Native American imagery has its roots in artifacts produced around the same time, and where ceramics may have first been produced in the New World a bit later. If my suspicions are true, much of today's imagery has its roots in the desert and mountains of a Peruvian/Ecuadorian society that existed between 5,000 and 3,000 BCE. Aspects of those ancient religions appear to have reached the Four Corners area in the early 1200s CE. Then in 1257 came a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia that blanketed the planet in volcanic ash for years. The sun disappeared into a dark gray sky and temperatures cooled, rain came pouring down, flash floods happened, crops failed and people starved. Then came years of crippling drought. That volcanic winter may have been the final turn of the screw in pushing the people of the Four Corners/Mesa Verde region to disperse and depopulate the area. Some American archaeologists have claimed they have found evidence of ritual human sacrifice and cannibalism in the Four Corners area from that time... but the practice (if it happened at all) never took hold and disappeared from the area very quickly. Aspects of the Flower World Complex may have been simply rejected back then but some of today's tribal religions still show residue from it. It's around the time of that mass out-migration that the Katsina, Warrior, Sacred Clown and Medicine societies seem to have come into being.

There is also speculation that cultivated maize may have first appeared in the diets of central Mexico around 3,000 BCE but archaeological evidence says the people of the northern Peruvian coast were growing 4 distinct varieties of maize by about 4,700 BCE: flour corn, corn used for chicha beer, ceremonial popcorn and corn for animal feed. That suggests that the cities of northern Peru shared trade with people in central Mexico, where maize is said to have first originated.

A couple more interesting things I came across: the avocado was being grown in northern Peru as much as 15,000 years ago, long before its first appearance in the Puebla, Mexico area about 8,000 years ago, and the people of the Caral/Supe region in Peru used vertebrae from blue whales to make sitting stools, more than 4,000 years ago.

The ancient Peruvian city of Caral has been touted as possibly the first great civilization in the New World but the ancient city of Bandurria has been dated to be a bit older, and the ruins at Huaca Prieta have been dated to be older yet (up to 14,000 BCE, within a thousand years or so of indigenous people first crossing the Bering Land Bridge from Asia to Alaska near the end of the last Ice Age). As excavations proceed in South America, the dawning of civilization in the New World gets pushed back earlier and earlier. Also, speculation is that the people of Caral were all equals, there were no elites, no religious or secular overlords. Those hierarchies came hundreds of years later, bringing with them wealth inequality, a military, taxes, religious rituals and eventually, human sacrifice.

Update: 2024. Near Lake Lucero at White Sands National Park in southern New Mexico, archaeologists discovered tracks of human footprints in sand between two layers of silt. The upper layer of silt was dated to have been laid down about 22,000 years ago, the lower layer about 23,500 years ago. The tracks are so well preserved that in one place, it's clear that the person was carrying a child: the child was set down on the sand for a few steps and left their footprints, too, before being picked up again. In those days, Lake Lucero had significant water in it and the area of the tracks is in what was a swamp along the shoreline at the time. The archaeological world is still digesting this but it seems to have changed everything.

A couple of the pyramids of Caral in 2004

How that knowledge, spirituality and technology made its way north over the next couple thousand years can be speculated on but the jungles and the activities of the more recent Spanish religious zealots between Peru and Mesoamerica have left precious little other than numerous stone constructions for us to examine and decipher. One thing, though: in the ruins of Caral a braided textile now known as a quipu was found, indicating those ancients had developed a method of recording tabular data for transmission cross-country and down through the generations. The decoding of a quipu was first accomplished only a few years ago and the data inscribed in it was as complex as any data stored in a modern spreadsheet, once someone knew how to read it.

Back to the Ceramic Story

Rodents can gnaw through a storage basket and quickly destroy any seeds or meals stored inside. A truly "hard" basket would stop that. A "hard" basket made for much more efficient cooking than a soft one, too. The idea was revolutionary and we can be sure it was opposed by those who made their living making and "selling" baskets. However, a "hard" basket can also crack or shatter. This trait made ceramic pottery a luxury to be enjoyed primarily by a more sedentary culture. The nomadic cultures of the Great Plains and the semi-nomadic Dineh, Ute and Apache of the Southwest never made much pottery pre-contact, although some Dineh potters today are creating some beautiful stuff, sealing it like they would a basket using the ancient swabbing-with-pine-pitch technique. Like the potters of Taos and Picuris, Jicarilla Apache potters also make micaceous pottery. There were native Dineh and Jicarilla Apache potters plying their craft several hundred years ago as their people became more agrarian and sedentary.

Some of the Pueblos (primarily in the Middle Rio Grande/Galisteo Basin area, near the ancient lead, silver and turquoise mines in the Cerrillos Hills) had discovered how to make paint glazes out of lead compounds and often decorated their ceremonial and household pottery with that before the Spanish invasion began. Bits and pieces of their pottery have been found from west of the Rio Grande to the Great Plains, from southern Colorado to northern Mexico. When the Spanish returned after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, they claimed the lead mines for themselves, to make lead shot for their primitive cannons and guns. Except for the Zunis, the tribes were denied nearly all access to those lead-silver sources. The nature of their pottery and its decorations changed almost overnight. The Zuni people had their own sources of lead-silver ore but when they saw what was happening in the Rio Grande area, they chose to lose that knowledge.

Closer to Home, Closer to Now

There were three centers of pottery production in Mexico by 1600 BCE: one in the Barra complex of coastal Chiapas, another in the Puron-Espiridion complex in the Tehuacan Valley and Oaxaca, and a third in the Chajil complex of northern Veracruz. A fourth one was developing in the area of Colima/Jalisco. In those days, the North American Southwest was mostly populated by indigenous Tanoan groups. It was Archaic times: hunter-gatherer basket-makers roaming the countryside with the seasons, the ripe fruits and berries, and the wild game, living in caves and pithouses.

Sometime around 200 CE, there were a couple movements north from Mexico, one east of the central Cordillera, the other west of the mountains along the coast and north into the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts. Those east of the mountains may have seeded the Tiwa as some Tiwa oral history says they came from the Aztec lands. Some of those who came through Sonora settled into the Tucson basin and became the first Hohokam. Those who went into the Mohave separated into several different directions. Some went north into the Great Basin. Some went east and followed the Colorado River upstream. Groups broke off from this and went north along the Virgin River, becoming the Virgin Anasazi and perhaps early Fremont. Others continued up the Colorado into the Grand Canyon, some staying there and some emerging along the Little Colorado River. Still others continued north to the San Juan River, and into what we now know as "Kayenta," and beyond.

Following the languages, the rock art, the architecture, the tools and weapons, archaeologists are pretty certain the first residents of the Hopi Mesas arrived there this way. Their oral history says they emerged into this world through a sipapu in the Grand Canyon, and then went in search of the best place for them to be, spiritually. The Hopi Mesas seem to have provided them with just the right amount of necessities and hardships to allow them to endure close to a thousand years of sometimes torrential rains and several multi-decade droughts in the same place, using mostly traditional technologies hundreds of years old, and more. Oraibi lays claim to being the oldest Hopi village still existing. It's been occupied for at least 800 years but because it's a living pueblo, no excavation has ever happened around it. There's little for the scientists to go on.

Walpi had another name when it was a village at the foot of the mesa instead of at the top. The oldest stories about Walpi emanate from that village at the foot of the mesa. There were several other villages nearby, around the foot of the mesa, when the elders of Walpi decided to relocate to the top of the mesa in an effort to avoid the Spanish. In order to accomplish the move in the time alloted, those villages that helped were allowed to live in Walpi after it was built. Those pueblos, all around the foot of First Mesa, were also then abandoned.

A trade with central and southern Mexico came into existence early, moving turquoise south and other goods and ideas north. That only grew as the people spread. Turquoise traced to mines in New Mexico, Arizona and southern Colorado has been found as far south as the Yucatan Peninsula and the Guatemala Highlands. It is along those routes that knowledge of ceramics, textiles and rituals most likely traveled. Textiles and ceramics (the shapes and the designs on them) were also closely tied to the prevailing religious system of the time-and-place of manufacture. That said, the only relics found in the Southwest that are positively attributed as coming from Mexico are seashells, coral beads, copper bells and the carcasses of macaws and white-fronted parrots.

Owing to the huge gap in the archaeological knowledge of northern Mexico, there are only guesses as to the locations and extent of trade routes and the establishment of any settlements along them. Not until the establishment of Paquimé and Casas Grandes, and their associated rancherias and homesteads. But that began roughly around 1150 and ended about 1450 CE. 1150 was during the time of the earliest migration of Kayenta potters to the south. There was another migration south in the mid 1200s (the Salado Phenomenon) and a return north in the mid 1400s.

The earliest ceramics unearthed so far in the North American Southwest were simple, rough ceramic figures, dated to somewhere between 800 BCE and 200 CE. They were found in the San Pedro Valley in southern Arizona, site of the first identifiable Hohokam settlements. These were also the sites of the first Hohokam irrigation projects. As time went on, their irrigation technology improved, as did their ceramic technology. Pottery came more and more into common use, not just for ceremonies but for cooking, serving and storage purposes. The estimate is that somewhere between 50 and 350 CE ceramic technology spread across the Southwest and by 500 CE, the need for storage vessels had become so great, people were making pottery almost everywhere. There were some areas in the Southwest where the folks were working hard to retain more of their indigenous spirituality and actively resisted new technologies and what they represented. In many cases, that resistance was likely triggered by the religious/ceremonial aspects that came hand-in-hand with some new pottery technologies [such as the Salado Phenomenon].

Around 300 CE, the northernmost endpoints of the turquoise trails seem to have been around the southern Gila Mountains in southern New Mexico and the valley of the San Pedro in southern Arizona. That's also about the same time the first finished ceramics were produced in those areas. By 450 CE the technology had reached Chaco Canyon and by 500 CE, it had reached the lower San Juan River area in southeastern Utah.

Where it Began in the Southwest

All the "recognized" early cultures of the Southwest: the Mogollon, Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloans made pottery. There were even potters among the Yuman peoples who populated the desert areas west of the Colorado River, but their work was more crude and primarily revolved around ceremonial figurative shapes. Archaeologists are pretty certain that most modern Puebloan potters are descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans but long and large migrations of families, clans and tribes occurred often over the last couple thousand years. Archaeologists feel that the movement of materials and technologies was mostly from south to north along established trade routes. Irrigation seems to have been worked out by the Hohokam people in the desert of southeast Arizona and expanded across the Valley of the Sun. As a sedentery agricultural people, their population expanded with their ease of feeding them all until around 1000 CE when they spilled over into other basins, like the Tonto Basin, Montezuma Well and the Verde River Valley. Further to the east and northeast were settlements of the Jornada Mogollon. Beyond them were Zuni and Chaco Canyon. To the north were settlements of the Kayenta people. The technologies of irrigation and pottery had been spreading among those people for several hundred years.

"Mogollon" is a reference to the Mogollon Rim, a geologic feature that extends from the western edge of the Gila Mountains northwest, across eastern Arizona to the western side of the Grand Canyon. Basically, it's the southern boundary of the Colorado Plateau uplift, an event that occurred around 65 million years ago and pushed the Colorado Plateau up several thousand feet above its surrounding countryside. There are places in Arizona where the rim drops 2,000 feet from heavily treed pine forest to stark desert vegetation in only a few miles. The first people now identified as "Mogollon" most likely lived in some of the ancient pithouses and pueblos found all through the region of the Mogollon Rim. Because of certain other similarities (room-block orientation, style of construction, square-vs-round kiva, pottery styles and decorations), the "boundary" of "Mogollon culture" has been extended to the south, through the Mimbres River Valley and San Andres Mountains to Paquimé and Casas Grandes, then slightly west and south to Aztitlan on the west coast of Mexico.

The Chaco Phenomenon has been well researched and documented. They had a lot of influence over a large area back then but the people of the Kayenta countryside were not interested. The folks in Kayenta country developed their own societies, built their own trade systems. For a couple hundred years they flourished, making San Juan Redware and trading it as far away as Mesa Verde (40 miles away). Then came a serious bout of bad weather in the 900s. Many of the people migrated to the east, to the highlands of Mesa Verde. There they had enough moisture from the sky that their dryland agricultural techniques were enough to keep them fed. The entire Lower San Juan area was depopulated and production of the famous redware resumed only sporadically until it completely ended around 1150.

Over the years, some of the people leaving Chaco went south. There's a 50-year period around 1000 CE where suddenly, several thousand people came over the hills from the north and moved into the upper Tularosa River drainage. Pithouses immediately gave way to above-ground, stacked masonry architecture, and the shapes and designs on pottery changed almost overnight. 50 years later the center of that population haved moved down the Tularosa River drainage toward what is now Reserve. 50 years after that, most of their descendants had moved into eastern Arizona.

The mid-1100s was also a time of bad weather, so bad the people were depleting their stores of corn and beans, then attacking the neighbors to try to steal theirs. The weather improved toward the end of the 1100s, only to get really bad again after Mount Sambolas exploded in Indonesia in 1257 CE. The sky was dark for several years and the rain poured down. Then the flooding stopped and things started to dry up. Officially, the Great Drought began in 1276 and ravaged the countryside for 20 years. Officially, that was the impetus for everyone to migrate out of the Four Corners/Mesa Verde area. However, people had already been leaving the area since the sky went dark, 20 years before.

The first Great Houses were built in Chaco Canyon in the 800s CE and construction of those and others continued until about 1125. The valley could only support so many people and things went well in the early days of a warmer and wetter weather trend. Then around 950 CE things started to cool and dry. The pueblo at Aztec (on the banks of the Animas River) was begun around 1000 CE and archaeologists say most administrative duties at Chaco were transferred to Aztec by 1100. Chaco itself was essentially empty of people before 1200 CE. Many of the Chaco people went to Mesa Verde and reoccupied pueblos that had been abandoned there 100 years before when the weather got warmer and wetter and their ancestors had migrated back to lower elevations (like Chaco Canyon). By the late 1200s, Aztec and the Mesa Verde area were again depopulated.

Some of those who left Chaco went south, to the area of Laguna where they set up on the shores of a large lake and wetland area (the lake was still there when the Spanish arrived several centuries later). A century after the founding of Laguna, migrants from the more northerly Kayenta lands appeared. Some of them settled upstream from the Lagunas, eventually reaching the foot of a white mesa they named Aaku, which they shortly built a new village on top of. Another century and the flow out of Mesa Verde saw groups moving southeast to build a pueblo at Gallinas Spring and another at a site called Pinnacle on the east side of the Black Mountains. They built other, smaller living spaces around the countryside, too, but by the early 1400s, all were abandoned and the area deserted.

The Mogollon people occupied the valleys and floodplains of the San Andres, Black and Gila Mountains areas in southern New Mexico. Because of similarities in pueblo and kiva construction, it is felt their culture extended northwest along the Mogollon Rim into eastern Arizona. The Mimbres Mogollon people came from the Mimbres River Valley and the Gila Mountains. When they migrated out from those mountains in the early-and-mid 1100s, some of them went to already established pueblos in the San Andres Mountains area in south-central New Mexico. Some went north, around the Black Mountains and into the area of today's Acoma and Laguna Pueblos. Others went south, to Paquimé and Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. A cultural group who lived in a strip along the Mogollon Rim in eastern Arizona are also classed as Jornada Mogollon. In some places the uplift was only about 800 feet, in other places it was 2,000 feet. It was a sharp, sudden, dramatic uplift and the millions of years of erosion since have only made the landscape more dramatic. The people of the Salado Phenomenon lived downhill on the edge of the Rim, in the Roosevelt Valley and Sierra Ancha Mountains. In the mid 1200s there was a migratory movement of Kayenta people into the Tonto Basin. Around 1400 CE there was a migratory movement out of the Salado centers, headed back north and into the Zuni, Hopi and Acoma areas.

Population in the Southwest fell off drastically in the 900s, then rose only to fall off precipitously again in the 1100s (severe drought from 1130 to 1180). Then the population rose again until it plateaued in the mid 1200s (drought from 1276 to 1299). Mount Sambolas erupted in Indonesia in 1257 CE and the whole world was plunged into darkness for several years. There was a steep decline in population everywhere. By 1450 the largest centers of population in the Southwest were in the Jemez Mountains/Pajarito Plateau/northern Rio Grande area with smaller centers in the Estancia Valley and along the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau, around Acoma, along the Zuni River in western New Mexico, and around the Hopi mesas in northeastern Arizona. The Hohokam heartland was almost completely deserted.

Between 1250 and about 1400, the Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, Tsegi Canyon, Homol'ovi and Aztec pueblos were abandoned. Some of the people went to the Hopi mesas and settled. Some went further south, eventually making their way into northern Mexico. A few others went east and southeast, eventually reaching areas already settled along the Rio Grande. Everywhere they went, there were already people living. Some settlements they merged with, others they fought and conquered. Some they fought and lost, and were forced to move on. These were also the years of the Sinagua culture and the Salado Phenomenon, from beginning to end. The 1400s were the time of the Gathering of Clans, the time when a Hopi identity began to come together.

For some, the journey down to the Rio Grande took several hundred years, for others only a hundred years. The Upper San Juan Valley, the Jemez Mountains and the Pajarito Plateau caused many of them to make several decades-long stops along the way. The valley of the Rio Grande was also heavily occupied by other peoples, some of whom were easy to melt into and some not so easy. The 1200s were also the time of the arrival of the first bands of Athabaskans from the north. Bands of Navajos started to arrive around 1400 CE. Other Apachean groups were making their way down the eastern slopes of the mountains and either south into Texas or west into the depopulated areas of the Gila Mountains and eastern Arizona.

Around 1350 a village we now call "Pottery Mound" began to grow along the Rio Puerco in central New Mexico. Those first villagers might have been Mimbres Nogollon people, moving north from the Gila Mountains area. They could just as easily have been Tiwas from Isleta meeting up with migrants from the Rio Salado pueblos in Arizona. However it happened, Pottery Mound was a melting pot of ideas and spirituality at a time when new clans were emerging among the Pueblo people.

Between about 1395 and 1415 CE, groups from Acoma and Zuni arrived at Pottery Mound. Between about 1405 and 1435, groups arrived from the Antelope Mesa area of Tusayan (the Spanish name for the Hopi mesas). Excavations at Pottery Mound have shown it to have been a melting pot of shapes, forms and designs. Some types of pottery never left the village while other types were offered in trade for hundreds of miles around. When the village was abandoned, between about 1475 and the early 1500s, families and clans (with their potters) returned to wherever they had come from before (except the Mimbres Mogollon: they seem to have gone mostly to nearby Acoma and Laguna). Those migrants took what had developed at Pottery Mound with them, and built on it from there.

Techniques such as slipping and painting a vessel were well developed 800 years ago and have changed little since. The pueblo potters suffered a severe hit under the onslaught of Spanish colonization. In the aftermath of the Spanish reconquest of New Mexico in the latter 1690s, the potters who'd had access to lead-silver ores and made glaze-painted pottery lost that access. The Spanish claimed all lead-silver sources for the manufacture of lead shot for their weapons. That was the end of a profitable business for the potters near the Cerrillos Hills. The Keres of the Galisteo Creek drainage made their way down to and merged into Santo Domingo. Within a few years the Southern Tewas of the Santa Fe River Basin had relocated to First Mesa in Hopiland. The people of Cochiti and Santo Domingo were able to restart their pottery-making process using different surface treatments and designs. The people of San Felipe didn't. Within a few years there was no design vocabulary at San Felipe: they were making only a few utilitarian pieces, trading instead with Zia Pueblo for most of their pottery needs.

The same for the people of Jemez. They resisted the Spanish so strongly and for so long that, in the end, all their traditions were almost completely destroyed. They were reduced from maybe 30,000 people to less than 3,000. They were forced to relocate to one village in the bottom of the canyon and they have never recovered. Today's Jemez pottery tradition seems to be determined by the colors of the clays used, not by any particular shapes, forms or designs.

A lot more was forgotten when the Euro-American pioneers pushing westward nearly destroyed what was left of the art of pottery-making in the pueblos. Cheap and easy-to-use glazed vessels and metal cookware became available in quantity to the Puebloans when traders and then the railroads began to infiltrate the Southwest in the mid and late 1800s.

How it Began Again

One story that has been little told is of how the onslaught of American "anthropologists," "ethnographers," "archaeologists," "collectors," traders and missionaries removed so much of the history and patrimony of the Southwestern tribes that some have none left. There is more ancient and early contact Native American pottery hidden in the basement of Harvard's Peabody Museum than there is on display anywhere. So much pottery was removed from the living pueblos and from their ancient ancestors homes that some have no traditional pottery to recover their past from. Most of the financially-backed looters excused their deeds and greed by saying (and believing) that they were saving the last few remnants of a dying people's art by placing it safely under the care of their respective universities and museums. Other looters were more honest: they were only in it for the money... and the looters came from all over the Western world of the time. Today's looters are still in it for the money and they seem to mostly operate out of homesteads in the Four Corners region. Instead of riding in on horseback and poking around for a few days with a pick and shovel, today's looters find their sites using Google Earth and dash around in helicopters like Special Forces commandos doing raids behind enemy lines. And the black market they feed just seems to keep growing and growing.

At San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh, someone digging a house basement on the west side of the Rio Grande in the 1920s stumbled across a pueblo ruin with some whole pieces of pottery in it. That pre-contact pottery was used as a basis to determine a truly traditional Ohkay Owingeh pottery form and design vocabulary (now known as Potsuwi'i, after the village ruin). At Hopi it was Nampeyo of Hano who essentially reconstructed shapes and designs from pottery found at the ancient sites of Sikyátki and Awat'ovi. She also brought in pre-contact designs from the Fourmile Ranch and Tsegi Canyon areas and combined those with designs first found at Payupki (where Western Keresans and Southern Tiwas hid from the Spanish for 60 years before they were convinced to abandon the village in the 1740s and return to the Rio Grande Valley).

At most other pueblos, modern potters only have the designs they find on the broken ancient potsherds littering the ground around their villages to work with. And if the main village of the people has been forced to move since Spanish contact, there is precious little of that, either. Thomas Tenorio told me he got his first designs from a book of hand-drawn Santo Domingo designs authored by Kenneth Chapman in the early 1900s. Josephine Nahohai was awarded an expenses-paid trip to the Smithsonian Institute and took most of her family along. They spent days copying ancient Zuni designs off the pottery they found in the storerooms there. Other potters vie for the Durbin Fellowship to the School for Advanced Research. That offers them 90 days of artist-in-residence privileges. Most spend a good part of that time in the vaults, copying designs from the ancient pottery stored there. Franklin Peters told me he spent so much time making drawings in the vaults that he doesn't remember what else he did the whole time.

Thankfully, Puebloan pottery is not now (nor likely ever was) a purely utilitarian item: in the pueblos, pottery has a spirit. It is a product of Mother Earth and her body forms the vessel and her bounty provides both the paints to decorate it with and the very need for creating the pottery in the first place. The children of Mother Earth who create pottery are aware of that spirit in the clay, in the paint, and ultimately in the spiritual synergy of the created vessel itself. The making of pottery is an integral aspect of their spirituality, especially should they be making ceremonial pottery.

Ceremonial pottery carries special designs on it that aren't supposed to be seen by anyone not directly initiated into the rites of the particular clan. Before the 1890s, it was often made and reused a number of times before being destroyed. Then came James and Matilda Cox Stephenson to Zia around 1890. He somehow saw a pot with the famous Zia sun symbol on it and he started negotiating to buy it. Within a few days he was dead under mysterious circumstances and Matilda had left to return to Washington DC. The pot was removed from the Zia Fire Clan's sacred kiva shortly after that and disappeared. It next appeared in artist Andrew Dasburg's home in Santa Fe, then disappeared again before being found at the School for Advanced Research, housed back then in the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe (the same structure where the Spanish had holed up in the beginning of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt). The pot was finally returned to Zia's Fire Clan in 2000, well after the sun symbol on it had appeared on the state flag and well after it started appearing in places as disparate as a Credit Union's logo, an Eastern New Mexico University sports team logo, the flag of the city of Madison, Wisconsin, on a plumbing company's trucks and on the sides of many portable toilets serviced by another company based in Albuquerque. Since about 1895, all the pueblo clans began destroying their ceremonial pottery after each use, and making new for the next ceremonies.

In the traditional way, there are songs and prayers to accompany each step in the process of creating a sacred pot. It begins with an offering of cornmeal to the Clay Mother before digging any clay and ends with breathing life into the finished piece after the firing. And all pots are sacred, even the flawed and broken ones. It is the awareness of this spirit that has kept pottery-making from being lost completely in favor of lesser spiritual quality but more durable and efficient wares.

While the Puebloans were treated brutally by the Spanish and their priests, enslaved and forced to convert to Franciscan Catholicism, their religion and their culture was not completely stamped out. Their spiritual practices, their languages and their cultures went underground. Most have endured with little change over the centuries.

When the United States took possession of the Southwest from Mexico in 1848, they largely ignored the pueblos as the pueblos were seemingly not as warlike as the nomadic Apache, Comanche, Kiowa and Dineh. They didn't terrorize homesteaders and settlers like the nomadic tribes did. The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo also confirmed the pueblos as distinct sovereign entities officially recognized by the United States Government. Each had that kind of agreement in place with Spain and Mexico long before the "Americans" arrived.

It's only in the most recent decades that the Puebloan culture has been truly threatened. As tiny islands in the ocean of an alien culture, the Pueblos are finding their youth less willing to learn and speak their native tongues, less willing to learn the traditional techniques of living in harmony with the Earth, and less willing to learn the complex and morally strict rites of the kivas.

Despite this trend, Pueblo pottery-making is in the middle of its greatest renaissance. The arrival of the new Euro-Americans created another function for pottery as it became a salable commodity on a scale never known before. The basic beauty in the shapes, forms and decorations of Puebloan pottery was not lost on the new settlers and traveling Easterners. Potters found the market for their wares growing in the twentieth century, but they had to get past the impression made by the quickly made and poorly painted "tourist pot" of the early twentieth century.

The "tourist pot" had come about as employees of the railroad barons solicited the potters of Acoma, Zuni and Hopi to churn out thousands of pieces of decidedly inferior quality. The art of pottery-making declined to being a basic mechanical function in the pueblos and soon, even the highest quality, well-made pieces themselves sold for next to nothing. It was individual traders who personally encouraged the potters to make more pieces of the quality of the vessels normally used in Pueblo ceremonies. The early traders were always the buffers and liaisons between the cultures and they played a tremendous role in cultivating general American appreciation for Native American art. Then again, there were some individual traders who essentially steered a pueblo's potters into making what became a progressively inferior (and dead-end) product, such as happened at Tesuque Pueblo with Jake Gold and the Rain Gods.

Pueblo Pottery as Art

Before 1950 only a few Native American potters signed their work. In their own communities, the forms and designs of their pieces made identifying the work of a master potter easy. Regionally, traders, collectors and museums also learned to differentiate these pieces.

In the twentieth century, benefactors from each of these categories organized a campaign to make the artistry and beauty of these vessels and their creators known to the world. Formal judging contests such as the Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial and the prestigious Santa Fe Indian Market that awarded ribbons and prizes for exceptional artistry began to have an impact. The early success and recognition of San Ildefonso Pueblo potter Maria Martinez at the St. Louis, San Diego and Chicago World Fairs began to open the door for other exceptional Native American potters. In the last decades of the 20th century the art and names of Pueblo pottery artists like Maria Martinez, Lucy Lewis, Christina Naranjo, Fannie Nampeyo, and Margaret Tafoya became known worldwide. Modern exhibitions like the Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery, permanent recognition in important museums around the world, and the marketing techniques of the traders and other Native American arts dealers has further cemented these names and the names of many, many other fine and deserving potters, both historic and contemporary, in the annals of art history.

As you look through this site you'll quickly see that each pueblo has its own style of pottery and designs, even when it comes to "contemporary" designs. Further, each potter and family of potters has its own styles and designs. Each succeeding generation sees potters becoming more and more specialized in their products: storyteller makers don't often make large jars, and vice versa. Everyone does traditional designs but not everyone incorporates contemporary designs. And slowly the electric kiln is creeping in...

PS: As I lift my eyes to the horizon (from almost strictly Puebloan pottery) I'm looking into pottery that has been produced by other Native American people. The distribution is from one end of the continent to another. That said, most lost their pottery traditions long ago, often in the periods of disruption following the invasion of Euro-Americans and the ensuing upheavals and forced migrations. Only now is some of the tradition being restored.

PPS: After all the above is said, there is still a lot unsaid. In the old days, the making of pottery was a community endeavor. Clay was sacred and belonged to the clan and the community, not to any individual. The clay was worked together with the potters teaching each other and innovating together. Someone who was judged better at making water jars was in charge of making water jars and passing that knowledge on to the next generation. Same for those who made bowls, cooking pots, storage jars and utensils. Decorating those pieces was the final touch before firing them. Firing was another part of the process shared among the potters.

This method of producing finely decorated utilitarian and ceremonial pottery was still practiced in the pueblos into the early 1900s. It was only after pieces began to be made for the commercial market and began to be signed by individual potters that everything changed. Today's potters are just as eager to share their knowledge as the potters of old. The problem is there are so few who want that knowledge passed to them.

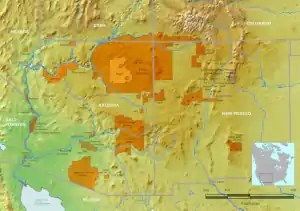

Map of Native American Reservations in the Southwest

Other photos and maps are in the public domain